At numerous points in the watching of Lincoln, Steven Spielburg’s new ode to America and Americana, I was reminded of Tableau Vivant, a kind of staged group charades that was a popular entertainment of the 19th century. In Tableau Vivant, costumed enactors wordlessly enact a story, freezing in a series of familiar scenes or attitudes.

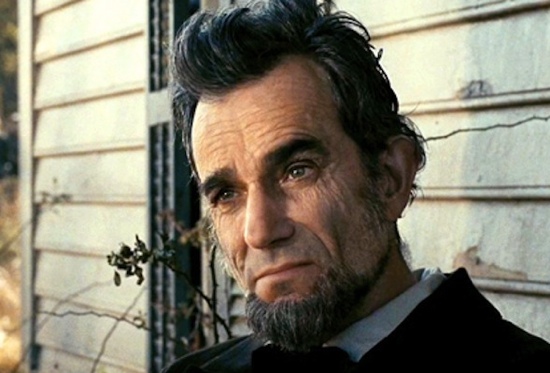

And so is the same in Lincoln, in which actors, led by an astonishingly physically like Daniel Day Lewis, enact the last several months of Abraham Lincoln’s life, frequently freezing in scenes or postures that seem designed to recall all the many paintings, daguerrotypes, statuary and coinage with which we are all so familiar and that pay homage to the man whom most agree is our country’s greatest president.

Despite the dramatic build-up around the central accomplishment of Lincoln’s severely truncated second term—the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery—and the political sausage-making this necessitates, the film feels less story than hagiography. Spielberg seems determined to convince us that Lincoln was a great president, and I buy it, but was it ever in question? Is this biopic or is it a nearly 3-hour Franklin Mint commercial? There’s been a lot of press about Lewis’s voice in this movie, but to me his entire performance, voice included, is problematic.

While everyone else around him proceeds in a naturalistic and lively manner—Sally Fields’s Mary Todd Lincoln and David Strathairn’s Secretary of State William Seward are especially fine—Lewis plays Lincoln with such stiff gait, strained falsetto and labored speech rhythms that he gives the impression of a giant marionette hiding amid humanity. He has limited himself to a handful of emotional channels, all as familiar to us from schoolbooks and the like as our own. There’s righteous determination, righteous indignation, fatherly devotion, melancholy brooding and twinkling tall tale-telling.

It seemed a sign that the cover story of New York Magazine the very week I saw this movie was entitled, “Is Everyone on the Autism Spectrum?” For this Lincoln seems always to dwell in his own gravity field, oblivious to the emotions and needs of others—a trait that helped him, after all, to doggedly pursue a constitutional amendment that others thought impossible to pass. This the film and Lewis do do well—show that Lincoln, while undoubtedly a great man, was apparently not, in our contemporary parlance, comfortable discussing feelings, his or others’.

When at a suspenseful point in emancipation proclamation campaign, Lincoln is asked serious questions, and rather than responding starts in instead on one of his homespun tales, an advisor bolts the room in disgust, yelling, “Not another story!” It’s one of the film’s funniest moments, and more so because it occurs at a juncture when one starts to feel sympathy for that fellow.

It doesn’t help that every twenty minutes or so Spielburg—and the very talented screenwriter/playwright Tony Kushner, who heavily adapted from the end of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Lincoln biography Team of Rivals, can’t resist the temptation to nearly halt the action for yet another iconic view of Lincoln, or yet another snippet of a speech we know so well. It’s very much like a fourth grade textbook coming to life, or like the world’s most expensive grade school Presidents Day pageant.

Of course we are nearly as familiar with the stories of Tad the youngest boy scandalizing senators by driving his goat cart in the White House and of Mary Todd scandalizing the public with her hysteria and profligate overspending, and these are playing out exactly per the national collective consciousness. Only thank goodness the masterful Field brings us intoMary Todd’s inner turmoil and humanizes a woman who is so often demonized, the ball and chain that kept Lincoln from floating off to heaven before his time. A theatrically wincing and limping Tommy Lee Jones and his comical wig share a flashy turn as raging Abolitionist Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens.

But the most pleasurable part of this otherwise stultifying film, by far, is that political sausage making and shockingly dirty deal-making that made the Emancipation Proclamation a constitutional reality. James Spader is fantastic as William Bilboe, a politically committed but morally liberal operative commissioned by Lincoln and Seward to wheel and deal behind the scenes. Plumped up, greasy, bug-eyed and disheveled, Spader is accorded no glowing cinematography or iconic angles and he emerges as its liveliest and most intriguing character. Friends, Romans, Countryman, lend me your ears; Steven Spielburg comes to praise Lincoln, but manages to bury him instead.